Courtesy of MyJewishLearning.

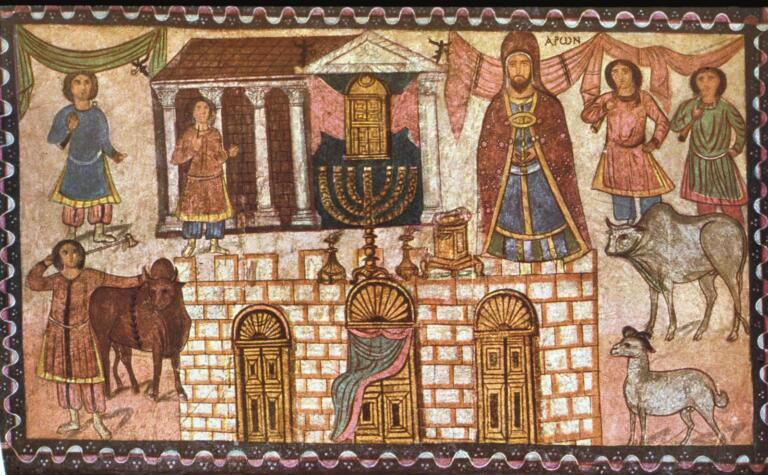

A painting of the Second Temple in the Dura-Europos Synagogue in Syria

By Rabbi Irving Greenberg

(MyJewishLearning) — On the ninth and 10th of the month of Av in the year 70, the Roman legions in Jerusalem smashed through the fortress tower of Antonia into the Holy Temple and set it afire. In the blackened remains of the sanctuary lay more than the ruins of the great Jewish revolt for political independence. To many Jews, it appeared that Judaism itself was shattered beyond repair.

Out of approximately four to five million Jews in the world, over a million died in that abortive war for independence. Many died of starvation, others by fire and crucifixion. So many Jews were sold into slavery and given over to the gladiatorial arenas and circuses that the price of slaves dropped precipitously, fulfilling the ancient curse: “There you will be offered for sale as slaves, and there will be no one willing to buy” (Deuteronomy 28:68). The destruction was preceded by events so devastating that they read like scenes out of the Holocaust.

Hear the words of the ancient Jewish historian, Josephus:

Famine: “Famine overcomes all other passions and is destructive of modesty… Wives pulled the morsels that their husbands were eating out of their very mouths and children did the same to their fathers and so did mothers to their infants, and when those that were most dear to them were perishing in their hands, they were not ashamed to take from them the very last drops of food that might have preserved their lives…”

Carnage: On the ninth day of Av: “One would have thought that the hill itself, on which the Temple stood, was seething hot from its base, it was so full of fire on every side; and yet the blood was larger in quantity than the fire, and those that were slain were more in number than those that slew them. For the ground was nowhere visible for the dead bodies that lay on it.”

Civil war between Jews: “The shouts of those [Jews] who were fighting [one another] were incessant both by day and night, but the continual lamentations of those who mourned were even more dreadful. Nor was any regard paid by relatives for those who were still alive. Nor was any care taken for the burial of those who were dead. The reason was that everyone despaired about himself.”

The exhaustion from all-out sacrifice of lives and fighting in vain was in itself debilitating, but the religious crisis was even worse. God’s own sanctuary, restored after the return to Zion in the sixth century B.C.E., the symbol of the unbroken covenant of Israel and God, was destroyed. This cast doubt on the very relationship of the people and their Lord. Had God rejected the covenant with Israel?

The Focal Point of Jewish Worship

The Temple was central to Jewish religious life in a way that is hard to recapture today. Many Jews believed that sin itself could be overcome only by bringing a sin offering in the Temple. Without such forgiveness, the sinner was condemned to alienation from God, which is equivalent to estrangement from valid existence. But the channel of sacrifice was now cut off.

For many Jews, the whole experience of Judaism was sacramental. The Priests served; the ignorant masses watched; their religious lives were illuminated only by those extraordinary moments when multitudes gathered in Jerusalem. There, in the awe of a Paschal sacrifice or at the Yom Kippur atonement ritual, they felt an emanation of divine force that showered grace and blessing on the people and made the Lord’s power a stunning presence. For these people, after the destruction there was only emptiness.

Responses to the Destruction

The majority of the Jews refused to quit. One element in this community reacted with overwhelming despair. The Talmud speaks of “mourners of Zion”who would neither eat meat nor drink wine. They rejected any possibility of normal life and chose not to marry or have children. Simple human activities — having a child, getting married, doing acts of kindness in a community — are sustained only by enormous levels of faith and life affirmation, and trust in ultimate meaning. Considering the tragedy and the threat that still hung over the Jewish community, these people felt they simply could not go on with life as usual. Yet by refusing to live normally, they harnessed despair into a force for action: to make an all-out effort to restore the Temple. Only rebuilding the sanctuary could reduce the terrible angst and restore life to normal.

The two major remaining sects, the Pharisees and the Sadducees, shared a common conviction that the Temple must be rebuilt, although the Sadducees, who included the court nobility and priests, were particularly unable to envision Judaism without a Temple. This consensus drove people to drastic action. In the years 115 to 117 C.E., there were widespread rebellions by Diaspora Jewry, which were bloodily suppressed.

In 132 C.E., the remaining population of Judea revolted, led by Simon Bar Kochba. But again, the overwhelming might of Rome was brought to bear. Bar Kochba and his troops were destroyed, and the remaining population of Judea was deported. With this defeat, hopes for an immediate restoration of the Temple were set back indefinitely.

Reprinted with permission of the author from The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays.