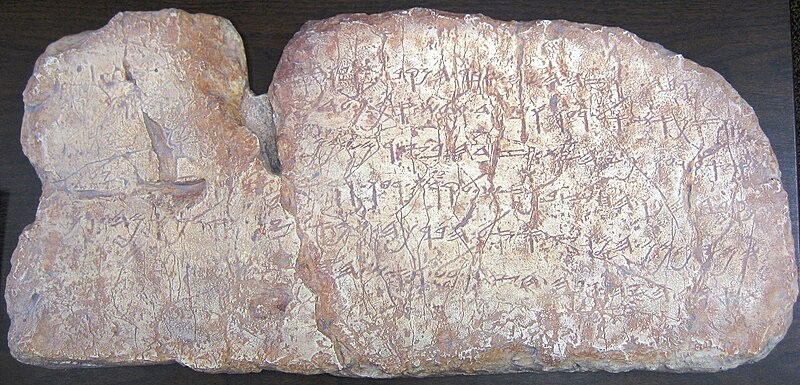

A replica of the Siloam Inscription

By Julia Olson

Assistant Editor

One of the first international stories that drew my interest just after I started at The American Israelite in 2022 was about the possible return of an ancient inscription from Turkey to Israel. The Times of Israel ran an article on March 11, 2022 stating that Turkey had agreed to return the Siloam Inscription to Jerusalem. As a student of ancient Middle Eastern history, I was excited to see my field of study intersect with my new job here at the newspaper. The story highlighted a very intricate issue about the ownership of cultural heritage and how modern international politics affect that ownership.

Of course, I do not expect you, the reader, to recall this news item from 2022. I’ll do my best to refresh you on it. But first, we should dig into what the Siloam Inscription is and what significance it plays in understanding the history of Israel.

If you have ever been to Jerusalem, you probably know that there are several ancient tunnels that stretch through parts of the city. One of these tunnels is known as “Hezekiah’s Tunnel.” You might remember my discussion of this tunnel in a previous column about the Assyrian king Sennacherib’s invasion of Judah in 701 B.C.E. According to stories in both 2 Kings 20 and 2 Chronicles 32, when Hezekiah heard that Sennacherib was approaching with his massive army, the Judean king ordered the tunnel dug so that he could divert water away from the Assyrian troops. Sieges could last for weeks, months, or even years, so a besieging army needed a nearby water source to keep up its strength and continue the occupation. The Chronicler depicts Hezekiah’s decision to divert the water as a noble one, painting him as a keen strategist and, of course, a (mostly) righteous king.

Photo courtesy of Tamar Hayardeni, C.C.3.0.

The Siloam Tunnel

But we must ask ourselves — how does one date a tunnel? After all, a tunnel is the absence of something. Dating tool marks on the wall from pickaxes is impossible, so how can we be sure that this tunnel is the one ordered by Hezekiah?

The tunnel roughly corresponds to the locations described in the Hebrew Bible and may have served in diverting the water from the Gihon Spring into the city. BUT — and this is critical — there were many attempted sieges in the history of Jerusalem. At any time, a king may have ordered the tunnel dug. On top of that, historians Rogerson and Davies have argued that the tunnel itself does not properly divert the water and the construction of such a tunnel would have actually drawn the attention of the invading army to the spring rather than denying them hydration (Rogerson and Davies, 1996).

The story of Hezekiah’s tunnel may be a sort of “etiology,” or an explanation of a thing that was already there. This is especially true if the story of Sennacherib’s invasion and Hezekiah’s response was written long after the event took place.

It’s important for historians to recognize the gray area that comes from interpreting the archaeological evidence in tandem with an ancient text. We can discuss plausibility when it comes to different interpretations of the correspondence between archaeology and text, but we should be wary of anyone who is willing to state something definitively! That’s the beauty of ancient history — we are allowed to entertain different ideas based on the same data. This makes for a robust discussion, which is the whole point of historical exploration!

But I digress. Let us return to Hezekiah’s Tunnel, which is also called the Siloam tunnel or the Silwan tunnel (because of its location in the Silwan neighborhood of East Jerusalem).

As the story goes, the tunnel was explored by an American scholar named Edward Robinson. While he was investigating the tunnel, he found writing inscribed in the wall. The inscription, though carved into stone, is very dynamic. It describes the cutting of the tunnel by the stonemasons themselves, and it even includes an action scene. Here is an excerpt:

And this is the narrative of the tunneling: While [the stone-cutters were wielding] the picks, each toward his co-worker, and while there were still three cubits to tunnel through, the voice of a man was heard calling out to his co-worker, because there was a fissure in the rock, running from south [to north]. And on the (final) day of tunneling, each of the stonecutters was striking (the stone) forcefully so as to meet his co-worker, pick after pick. And then the water began to flow from the source to the pool, a distance of 1200 cubits. And 100 cubits was the height of the rock above the head of the stone-cutters (Rollston, “Siloam Inscription”).

The brackets in the translation indicate broken or hard to read text. Rollston, the translator, is indicating to his readers that he has reconstructed those missing letters to render the translation.

Essentially, the author of the inscription is describing the moment where the pickaxes of the men tunneling from one side met with those of the men tunneling from the other. Talk about an action shot!

Of course, this is ancient history, so we have our usual amount of gray areas with which we must contend. First — literacy in the ancient world was very rare. It is not likely that a stonemason and his buddies were literate enough to inscribe this play-by-play account of their project onto the wall. This is not to say that stonemasons were not bright people! But writing and reading were skills taught only to the intellectual elite, and it was unlikely that a royal scribe was moonlighting as a tunnel-digging stonemason. Our second issue arises when we consider something called paleography. Paleography is the analysis of writing systems and the dating of ancient texts. And, you guessed it, the Siloam Inscription raises some issues for us paleographically (and not just because an illiterate stone mason might have written it). The language of the inscription is considered paleo-Hebrew (or very early Hebrew). There are parallel examples of paleo-Hebrew that date from 900 – 600 B.C.E., evidence which may bolster the claim that the Hebrew in the tunnel was written during that period. Remember, Hezekiah is said to have ordered the tunnel’s construction when Sennacherib came to town in 701 B.C.E. But, of course, this is ancient history, so there are more complex issues at hand! Authors in the ancient world often adapted earlier styles of writing to lend credibility to what they were saying or simply because they were interested in making their writing sound older and more archaic than it actually was. It would be like writing a legal document today in the language of the Declaration of Independence, or writing a love note to someone in the style of Chaucer. Ancient authors did things like this all the time! It makes dating their writings exceedingly difficult. Imagine an archaeologist, 1000 years from now, digging up a legal brief from 2024 written in the language of 1700s Colonial America. How would they interpret it? How would they date it? What conclusions would they draw about the authors who wrote it? Despite the fact that it relies on concrete written texts, even paleography is not a science but an interpretive art.

There is evidence of inscriptions from the Hasmonean period written in the same style of paleo-Hebrew found in the Siloam Inscription (Rogerson and Davies, 1996; McLean, 1982). So, you see, the text could reflect a more ancient time (900 – 600 B.C.E.) or it could be an ancient writing style adapted by a more recent writer during the Hasmonean period (140-37 B.C.E.).

This, of course, leads to a very spirited debate among Biblical scholars about what the inscription can tell us about the history of Jerusalem.

To put the cherry on the top, the translation and interpretation of the inscription is not even the end of its complexities! The Siloam Inscription also highlights modern political issues and the meaning of cultural heritage. Would you be surprised to learn that the inscription is now on display in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum in Istanbul, Turkey? It’s true.

The actual Siloam Inscription on display at the Istanbul Archaeological Museums

When Edward Robinson found the inscription, Jerusalem was under the control of the Ottoman Empire. Thus, any antiquities unearthed during that time were considered the property of the empire. The inscription was brought back to the Ottoman capital of Istanbul, where it has been on display ever since. The State of Israel has asked for the inscription back several times, but, each time, the Turkish government has denied the request. This is because Turkish officials consider East Jerusalem, where the inscription was found, part of the Palestinian territories. According to the Daily Sabah, a Turkish newspaper, the inscription is Palestinian cultural heritage and thus returning it to Israel, a third country is “out of the question” (Daily Sabah, March 13, 2022). So, an already complex ancient inscription is now part of an even more complex geopolitical issue. The Siloam Inscription is the perfect embodiment not only of the interpretive issues involved with ancient material, but of the major impact those ancient materials have on our modern world. This means that we, as historians, have an impact on the future based on how we interpret the past. The act of studying and interpreting history has real world importance and impacts how we interact with one another. Ancient history is not limited to old rocks, confusing inscriptions and dusty trowels. It is a key player in contemporary understandings of the world, of cultural heritage and the idea of ownership. That means that ancient historians are not only students of the past but contributors to the future as well. That a potentially 2,700 year old inscription is still hotly debated today is a clear example of this. And, rest assured, if the Siloam Inscription ever makes headlines again, I’ll report the latest developments to you!

Bibliography:

McLean, D.M., The Use and Development of Paleo-Hebrew in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods. Ph.D. diss.,1982, Harvard University.

Rogerson, John and Philip Davies. “Was the Siloam Tunnel Built by Hezekiah?” The Biblical Archaeologist Vol. 59 No.3 (Sept. 1996): 138-149

Christopher Rollston, “The Siloam Inscription and Hezekiah’s Tunnel,” Bible Odyssey.

Daily Sabah Staff, “Turkey denies return of inscription to Israel after Herzog visit,” Daily Sabah, March 13, 2022.

Shalom Yerushalmi, “Israeli official: Turkey agrees to return ancient Hebrew inscription to Jerusalem,” Times of Israel, March 11, 2022.