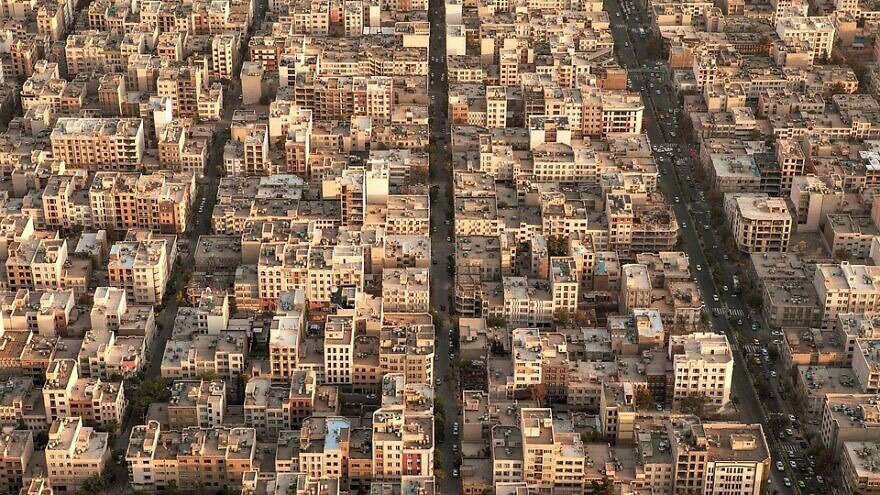

Courtesy of JNS. Photo credit: Pixabay

An overview of Tehran

(JNS) — For much of last week, Iran was “virtually shut down” to conserve energy, with the nation’s leaders offering no solution other than to say sorry, The New York Times reported on Dec. 21.

“We must apologize to the people that we are in a situation where they have to bear the brunt,” Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian said in a live televised address this month.

“We are facing very dire imbalances in gas, electricity, energy, water, money and environment. All of them are at a level that could turn into a crisis,” he said.

Power outages started during a heat wave in August and now have become a full-blown crisis. Government offices are shuttered or operating on reduced hours, schools are online-only and factories have lost power, “bringing manufacturing to a near halt,” the Times reported.

This, despite the fact that Iran is awash in natural gas and crude oil. (It ranks second in the world in natural gas reserves and fourth in oil reserves.)

Seventy percent of Iran’s energy comes from natural gas, with 90% of Iranians relying on gas for heating and cooking. Most Iranian power plants run on natural gas.

Iran needs about 350 million cubic meters of natural gas a day to function. With overnight winter temperatures in the 30s and 40s Fahrenheit, demand has spiked.

The government was faced with either cutting gas service to homes, or shutting down power to electric generation plants.

The former would cut heat to residents during the cold winter months, so the government chose the latter.

“The policy of the government is to prevent at all costs cutting gas and heat to homes,” Seyed Hamid Hosseini, a member of the Chamber of Commerce’s energy committee, told the Times. “They are scrambling to manage the crisis and contain the damage because this is like a powder keg that can explode and create unrest across the country.”

Seventeen power plants had been taken offline by Dec. 20. The rest are operating on a partial basis.

Tavanir, the state power company, said widespread power cuts could last days or weeks.

Mehdi Bostanchi, head of the country’s Coordination Council of Industries, told the Times that the situation was catastrophic and industries had never experienced anything like it.

He estimated last week’s power cuts could cut manufacturing in Iran by 30% to 50%, amounting to tens of billions of dollars. Smaller and medium factories were hit the hardest, he said.

Sanctions, mismanagement, aging infrastructure and wasteful consumption were reasons cited by the Times for the power crisis. It also listed targeted attacks by Israel, noting Israel’s destruction of two Iranian gas pipelines in February.

Iranians mainly blame the government.

“The Islamic Republic has set us back centuries and ruined our lives,” said one citizen quoted by Iranian International, an anti-government, London-based news outlet, on Nov. 20.

Corruption, mismanagement and foreign wars

According to the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies (FDD), a Washington-based think tank, “The people know the real cause is the regime’s unending corruption, mismanagement and foreign wars. Thus, the overwhelming majority blames [Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali] Khamenei and his lieutenants.”

Iran simply doesn’t produce enough electricity, FDD noted, saying consumption peaks at 17,500 megawatts above production, “a shortfall equivalent to more than eight Hoover Dams.”

The Islamic regime is blaming everyone but itself, sparking further anger among the population.

Pezeshkian claimed the blackouts are due to his decision to ban mazut, a type of low-cost fuel used in the Soviet-era, which is highly polluting.

But his ban affects only three out of 16 plants that burn the substance. “Nor does he explain why taking three plants offline would cause such shortages, as Iran has 140 other major power plants,” FDD said.

In any case, the government reversed its partial ban on the fuel in a Nov. 17 decision, “authorizing provinces to use mazut in all power plants and industries,” Iranian International reported.

The government also has accused the population of wasteful energy use, sparking even more anger among average Iranians.

In November, Mohammad-Jafar Ghaempanah, Pezeshkian’s executive deputy, blamed the public for the shortages and the mazut burning.

In September, Vahid Yaminpour, a state television presenter and secretary of the Supreme Council of Youth, called the power cuts a “positive event” that strengthens the family foundation, Iranian International reported.

“In Lebanon, even in non-war conditions, many people have about four hours of state electricity,” Yaminpour said. “Be grateful and don’t complain.”

His comments met with widespread criticism.

Hassanali Taghizadeh, chairman of the Iran Electrical Industry Syndicate, rejected the assertion that domestic use was disproportionately high, saying, “Don’t blame the people.”

One critic said: “There are donation boxes all over the cities to help the people of Gaza and Lebanon, while the officials of the Islamic Republic don’t care about the Iranian people at all.”

Another pointed out that unlike Lebanon, Iran is energy-rich.

A third said Iranian officials are unable to provide for their own people and only know how to launch missiles.