Submitted by Jewish Cemeteries of Greater Cincinnati

Jewish Hospital of Cincinnati was the very first hospital established by and especially for Jews in America. This is a distinction not many Cincinnatians know about our Jewish community. The founding year was 1850 and people were dying in a cholera epidemic. Jews and Jewish doctors were often not welcomed in other hospitals. Kosher food was unobtainable in them, and it was common for Jews to be pressured to take Christian conversion on their deathbeds.

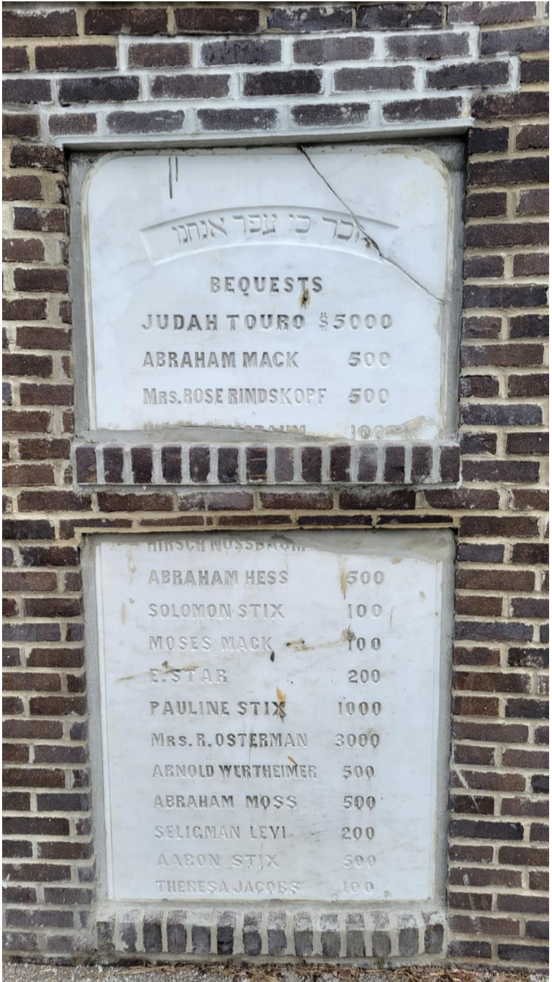

Jewish Hospital was and always has been welcoming to people of all faiths, but when it was founded before the Civil War, there was especial need to treat Jewish immigrants flocking to Cincinnati. After three decades passed, the hospital, which had occupied a series of smaller buildings around downtown, needed to expand. Its leaders asked the community to help, and as the plaque here shows, many recognizable individuals stepped forward with donations.

During the dedication in 1890, this plaque honoring those donors was proudly placed in the lobby of the vastly expanded Jewish Hospital, located on Burnet Avenue. Decades passed, with more donor plaques added as the hospital grew. This pictured plaque and the others were eventually taken down during a renovation, stored in the hospital basement and essentially forgotten.

In 2013, the hospital’s historic donor plaques were accepted for safekeeping by the Jewish Foundation. Now fully seven of the plaques, including this one pictured, form an entire wall of Jewish Hospital’s early philanthropic history which can be viewed at the installation “Foundations of Our Future” within Loveland Cemetery.

Many of the names on this particular plaque are familiar to us in Cincinnati because of the successful business and communal service legacies they left, too numerous to fully describe here. Their names can be seen on prominent monuments in Walnut Hills Cemetery; most were members of the growing new “Reform” Jewish community. Wertheimer began in whiskey distilling. Stix was in dry goods, and eventually U.S. Shoe. Mack, Nussbaum, Moss — these individuals and the others helped build Cincinnati and beyond.

Other names of large donors reveal interesting stories. Mrs. R. Osterman gave $3000, but indeed it came from her Texas estate, as Mrs. Rosanna Dyer Osterman had died twenty years earlier. She was a well-respected nurse before and during the Civil War, and the philanthropic wife of a founder of the Jewish community in Galveston, Texas. She never resided in Cincinnati, but her devotion to all Jewish communal institutions extended to our hospital.

Also prominent on the plaque, followed by the very large donation of $5,000 (equivalent to $168,000 today), is the name Judah Touro, not a Cincinnatian then or ever. His family arrived in America in the late 1700’s and gave its name to the impressive Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island. Judah Touro’s wealth was made as a merchant in New Orleans, where he was famed for his quiet generosity to needy individuals as well as to the community. After his death, his estate continued making sizable donations to Jewish (as well as non-Jewish) causes. This is likely how Cincinnati’s Jewish Hospital expansion received such a large gift, more than thirty years after Touro’s death.

The plaque was unfortunately broken in two during the move to the Jewish Cemeteries basement. Carrie Rhodus, Operations Manager of Jewish Cemeteries, says, “We chose to mount the two pieces of the plaque with the break’s gap made obvious. Part of the story is that these items have been forgotten for decades — manhandled, sometimes broken. We have taken on responsibility to honor and preserve them for the future.”

Inscribed on Touro’s tomb in 1854 were these words:

“By righteousness and integrity he collected his wealth;

In charity and for salvation he dispensed it.

The last of his name, he inscribed it in the book of philanthropy To be remembered forever.”

In his lifetime, Judah Touro strove to keep his giving behind a curtain of anonymity, as taught by Maimonides, but recipients of his generosity often named and praised him. In a sense, the fact that his name was inscribed on this plaque, alongside the names of Cincinnati Jews, might represent yet another blow to his humility.