By Julia Olson

Assistant Editor

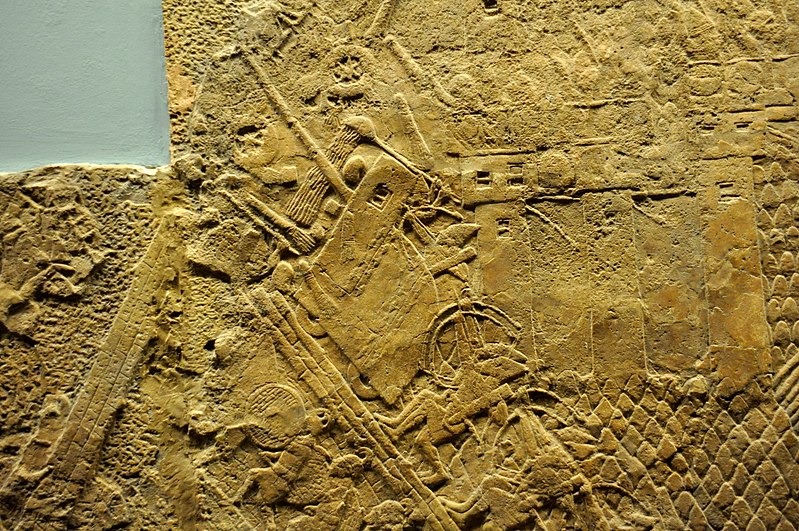

Photo Caption: Assyrian siege-engine attacking the city wall of Lachish. The ascending and assaulting Assyrian military wave is overwhelming. Detail of a gypsum wall relief dating back to the reign of Sennacherib, 700-692 BCE. From the South-West Palace at Nineveh, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq, currently housed in the British Museum, London.

The Assyrian Army was known across the ancient world for its power and ferocity. Before the Neo-Assyrians, it was common practice for farmers and merchants to act as a kingdom’s army. Fighting had to be seasonal, lest the farmers neglect their fields and invite economic ruin to the kingdom they were fighting to protect. This all changed, however, when Tiglath-Pilesar III (r. 745 – 727 BCE), developed the ancient Middle East’s first standing army. Now, instead of alternating war with sowing and harvesting, the Assyrian military could wage battle all year round.

The Assyrian Empire rapidly became known for its military prowess but more so for its brutality. Word of mouth from those the empire conquered would have contributed to this image, but the Assyrians were famous for depicting their military violence in large pictorial reliefs that survive today. For example, King Ashurnasirpal II, who reigned from 669 – 631 BCE, had himself depicted in a palace relief dining next to the severed head of an enemy Elamite king. The relief shows Ashurnasirpal lounging in his garden while the head of the Elamite king hangs nearby in a tree.

Certainly the power and brutality of the Assyrian army would have been well known in the ancient Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean. We must imagine, then, King Hezekiah’s horror when he heard that Sennacherib and his Assyrian army was marching toward the Mediterranean coast to seek payment for taxes and tributes unpaid in protest by the local kings of that region.

As we know from 2 Kings 18:7, Hezekiah was also guilty of withholding tribute from the Assyrian empire. The text states that “[Hezekiah] rebelled against the king of Assyria and did not serve him” (2 Kings 18:7). At that time, tribute was often paid to larger empires for protection (from other kingdoms as well as from the empire imposing the tribute). Imagine paying for “protection” from The Mob, for example, but on a much larger scale. Many kings saw the withholding of these payments as an act of war.

This is likely what brought Sennacherib to the Eastern Mediterranean coast around 701 BCE. In his annals, works in which the king Sennacherib recounts his military campaigns and building projects, among other elements of his rulership, he describes his army sweeping down the Levantine coast. He spends time in Syria, whose kings he forced to repay tribute and kiss his feet. He writes of conquering the major cities of Sidon (now in modern Lebanon) and proceeding down the Lebanese coast through Gubla (called Byblos in the Hebrew Bible) to Ashdod. Finally, after going far down what is now the southern coast of Israel, Sennacherib and his army turn northeast and set their sights on Jerusalem. Sennacherib mentions Hezekiah by name in his annals, describing him as “the one who did not submit to my yoke” (OI Prism, Col. III, Line 18). This likely indicates that Hezekiah did not pay tribute to Sennacherib and thus incurred the wrath of the king.

This event would seem fairly common in the historical field. We are no stranger to stories of vindictive kings, tributes unpaid, heroic underdogs coming out of the ancient world. But this particular instance provides historians with something we do not often have from ancient Middle Eastern historical battle records. For this event, the conflict between Sennacherib and Hezekiah, we have multiple accounts from different sources.

We have discussed already the narrative provided for us in Sennacherib’s annals. However, this story is recounted not once, not twice, but THREE TIMES in the Hebrew Bible as well! So rarely do we have such an abundance of testimony to a single historical event. The story is recounted in 2 Kings 18-19, 2 Chronicles 32, and Isaiah 36-37.

Of course, Sennacherib’s account and the accounts in the Hebrew Bible tell a different story. Sennacherib claims that he attacked 46 of Hezekiah’s fortified cities (cities with strong defensive walls) and took prisoners, animals, and other treasures. He also says that he shut up Hezekiah himself “like a caged bird” in the city of Jerusalem (OI Prism, Col. III, Lines 27-28). Sennacherib then claims he increased the amount of tribute that Hezekiah would have to pay. Eventually, according to the Assyrian king, Hezekiah paid gold, silver, and other precious gems as well as presenting his daughters and other courtiers for the Assyrian tribute payment. After he recounts this payment, Sennacherib moves on in his annals to describe a campaign at another site.

The Hebrew Bible, however, tells us a different story. In the 2 Kings account, Hezekiah admits his fault, apologizes to the king, admitting “I have done wrong. Withdraw from me and I will pay whatever you demand of me” (2 Kings 18:14). Then, he strips the temple of its silver and gold and gives that to the Assyrian king (2 Kings 18:15).

In the Isaiah account as well as in the 2 Chronicles account, however, Hezekiah admits no wrong and does not strip the temple. In fact, the Hezekiah of 2 Chronicles prepares for the siege, consulting with his military officials and planning the best way to prepare the city for the attack (2 Chron. 32:3). Hezekiah then diverts a spring into the city, which would keep the people in the city with fresh water and also prevent the Assyrian army from refreshing their troops with the spring. He builds a tunnel to bring the spring water into the city.

This may have actually happened, according to some archaeologists. Hezekiah’s Tunnel is a popular tourist attraction in Israel today, and is named because it may be the tunnel that Hezekiah constructed to divert the water into the city.

However, historians Rogerson and Davies disagree with this analysis, arguing the tunnel is from a much later period and that the mention of the tunnel in the text is merely coincidental (Rogerson, Davies, 1996).

What we do know is that, during the period around 701 BCE, when Sennacherib was on the attack in the region, a number of jar handles stamped with the Hebrew inscription “LMLK” were sent to the cities surrounding Jerusalem. More than 1200 of these handles have been found in Jerusalem, Lachish (a city that Sennacherib depicts sieging in greatly detailed relief panels in his Southwest Palace) and other sites. Material analysis shows us that they were all made in the same place (Grabbe, 2003).

The inscription LMLK means “of the king” and indicates that whatever the jars were full of were likely reinforcements that the capital city was sending out to surrounding towns so they could prepare for the siege. Remember, Sennacherib claims to have attacked 46 cities, so Hezekiah had quite a few jars of perhaps grain, oil, and other materials to send out. Since Hezekiah had withheld his tribute from Sennacherib, he very likely knew that a siege was coming. Once he decided to stop paying tribute, it is possible he started using these jars to stockpile resources (Grabbe, 2003).

In Sennacherib’s annals, he traps Hezekiah in the city of Jerusalem and forces him to pay tribute. Then he continues on his campaign, much wealthier as a result of his Judaean spoils. But in the Hebrew Bible, a far different outcome occurs. In the 2 Kings account, an angel of the Lord goes out among the Assyrian war camp and kills 185,000 troops, forcing Sennacherib to flee. The Isaiah account reports the same death toll. In 2 Chronicles, the Lord sends an angel who kills “all the fighting men and commanders and officers in the camp” (2 Chronicles 32:21). Each of the three accounts report a major death toll and Sennacherib’s immediate retreat back to Nineveh, Sennacherib’s capital city.

Interestingly, each account also tells us that, after returning home, Sennacherib goes to pray in the temple and is murdered by two of his sons.

While we do not know if this temple betrayal scene is actually true, Sennacherib was very likely murdered by his sons in their bid for succession to the throne.

So here we have multiple, competing accounts of the same event. Each is written according to the agenda of its author(s). We know that Sennacherib appeared in 701 BCE in the region and threatened king Hezekiah, who had not paid tribute. Sennacherib claims to have shut Hezekiah up in the city, however, we should note that he does not specifically say that he besieged the city of Jerusalem. He certainly attacked the cities around it, including Lachish, as we have archaeological evidence attesting to destruction (fires, collapsed walls, arrowheads) taking place at this time. But Sennacherib is not clear as to whether he besieged Jerusalem or simply threatened Hezekiah. There is no evidence yet uncovered in Jerusalem that attests to a siege in that city at that time. And we do know that, though he may have paid tribute to get Sennacherib to leave, Hezekiah certainly prepared his people with resources delivered in his LMLK jars. But this is where history is the most fun (or the most frustrating). Was the city of Jerusalem besieged by Sennacherib? Did Hezekiah build the tunnel? Did all of the Assyrian troops die in their military camp? As long as we have the evidence, we can come up with differing theories as to what actually happened. We may never know the real story! But we certainly can have fun exploring the different ways kings in power shared stories of their military escapades in the ancient world.

Resources:

Grabbe, Lester L., ed. “Like a Bird in a Cage”: The Invasion of Sennacherib in 701 BCE. Journal For the Study of the Old Testament 363. London; New York, NY: Sheffield Academic Press, 2003.

Rogerson, J., Davies, P. R., Was the Siloam Tunnel Built by Hezekiah?, Biblical Archaeologist 59, 1996, pp. 138–49.