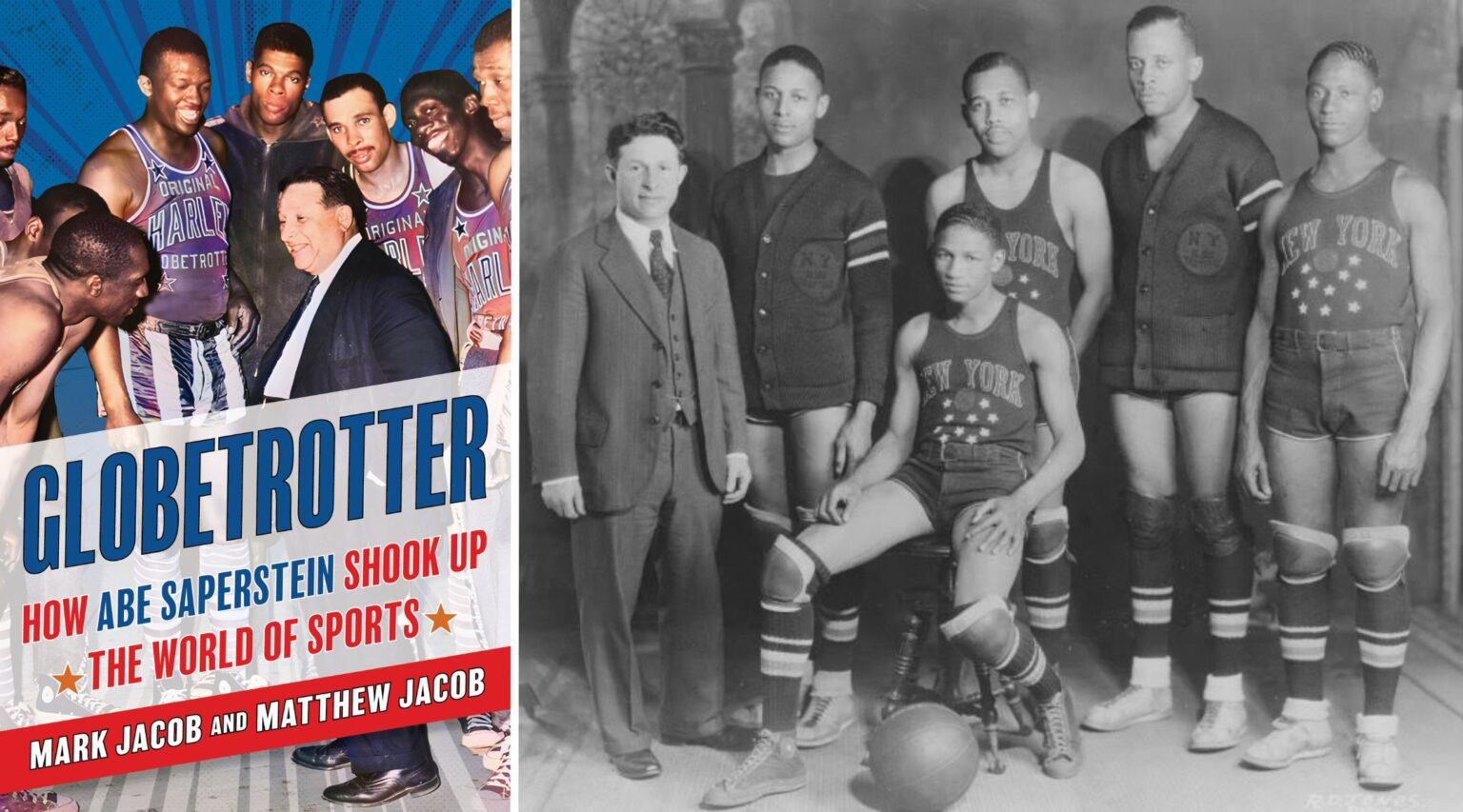

Courtesy of JTA. Photo credit: Berkley Family Collection

At left, the book cover of Mark and Matthew Jacob’s Abe Saperstein biography (Courtesy); at right, Saperstein, far left, in the earliest known team photo of the Globetrotters, from the 1930–1931 season

(JTA) —In a new book, “Globetrotter: How Abe Saperstein Shook Up the World of Sports,” brothers Mark and Matthew Jacob explore Saperstein’s far-reaching legacy, which they say is still under-appreciated 58 years after his death. In addition to the three-pointer, they contend, Saperstein played a crucial role in elevating basketball from a second-tier American sport to a professionalized global powerhouse.

Among his career highlights: He pushed the NBA to expand to the West Coast years before the Minneapolis Lakers moved to Los Angeles in 1960. And as early as the 1950s and ’60s, Saperstein warned about the slow pace of play in baseball, a live issue in MLB debates in recent years, and urged team owners to charge more for games against better teams.

“Globetrotter,” which hit shelves this week, is the result of years of research and writing by the Jacobs. Mark, 69, lives in Evanston, Illinois, and is a former editor at the Chicago Tribune; Matthew, 61, lives in Arlington, Virginia, and is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research, the group credited with revolutionizing that game through analytics. (The brothers are not Jewish.)

Saperstein was born on July 4, 1902, in London to Louis and Anna Saperstein, who had left what is now Poland amid a rise in antisemitism. The family moved to Chicago when Abe was 5.

Saperstein’s career in sports began as a booking agent, and in 1926 he became the coach of an all-Black team then called the Savoy Big Five, based on the South Side of Chicago. Saperstein renamed the team and began a barnstorming tour that, nearly a century and thousands of games later, the Globetrotters are still on.

At its inception, the team was neither from Harlem, nor were they globetrotters. The name was a symbol of Saperstein’s promotional flair: “Harlem” was chosen to signal to Midwestern towns of that era that the team was all-Black, and “Globetrotters” was meant to exaggerate the team’s reach and prestige.

The Globetrotters’ famous style of play — an entertaining combination of impressive athleticism, comedy and theatrics — has earned the team, and its founder, both celebration and consternation. While the Globetrotters are credited with elevating players such as Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton — who was one of the first Black players in the NBA — and future Hall of Famer Wilt Chamberlain, the team also took heat for what some considered to be playing into racist stereotypes.

But Jacob said the Globetrotters, and Saperstein, were far more nuanced than the team’s sometimes circus-like style would suggest. There was a reason Black icons including Jesse Owens and Jesse Jackson were fans.

It was Saperstein’s identity as an outsider — a Jewish immigrant from London — that helped him take on the role of a go-between for his Black players and the still mostly white world of professional sports. Mark Jacob said Saperstein fits into broader Jewish-Black relations in the period, when Jewish leaders played a key role in the fight for Black civil rights.

Saperstein, a proud Jew and Zionist, was also no stranger to discrimination himself.

As “Globetrotter” details, Saperstein and his family faced antisemitism time and again, in London, in Chicago and as Saperstein traveled the world promoting his Globetrotters, Negro League baseball teams and other Black athletes.

Saperstein’s Jewish identity was especially front and center during the Globetrotters’ first European tour in 1950. When the Globetrotters went to Paris, Saperstein was vocal about his disdain for a particular venue, the Palais des Sports, where just years earlier 30,000 Jews had been held before being deported to Nazi camps.

Saperstein and his 13-year-old daughter Eloise also encountered the deep-seated antisemitism of postwar Germany, according to a particularly powerful anecdote from the book recounted by Abra Berkley, Eloise’s daughter.

While her father conducted a news conference at a hotel, Eloise, in search of local Jewish food, went to the concierge to ask where she could find the Jewish neighborhood.

As Berkley recounted, the hotel worker spat in Eloise’s face and told her, “Hitler should have gotten rid of all of you.” Eloise, with spit still dripping down her face, burst into her father’s news conference, crying hysterically, and told him what happened.

Saperstein abruptly ended the conference, demanded the employee be fired, and went to a jeweler next door to order a Star of David necklace for Eloise, which Berkley said her mother never took off. Years later, Eloise made copies of the pendant for her own daughters.

“The fact that Abe went off and had that made right after that incident is just a very powerful message, not only to people today, but obviously to his daughter, who’s just gone through this very horrible experience,” said Matthew Jacob. “He is like, ‘This is who we are, and we’re going to be proud of it, and I don’t ever want you to forget it, because I won’t.’”

The scene, Mark Jacob said, exemplifies the audacity that animated Saperstein’s entire career, in which he was never afraid to speak his mind, even when some of his ideas were decades ahead of their time.

“Jews have historically faced horrible challenges and discrimination,” said Mark Jacob. “I think that there’s this kind of endurance, this ability to rise above circumstances and to meet challenges instead of avoiding them. And Abe was that. Abe did that.”